∧ Back to top3. Changes in glass manufacture

In the 17th century, the glass industry reduced its costs and increased the volume of production by adopting coal as its fuel. The Patent of Monopoly awarded to Mansell was conditional on the enforcement of this change in fuel, intended to reduce the demand for wood, on which industries such as iron-manufacture depended. The use of wood fuel for glass making ended during the years 1615-1620 (Godfrey 1974), with adaptation of the design of furnaces to burn coal (Crossley 1987). This change took place with a speed which is un-matched elsewhere in Europe. The glass industry ceased to be based in the forests and new furnaces were set up where coal was plentiful. Under the Mansell patent, which was in force until 1642, glass furnaces were built in the North East of England, around Newcastle-upon-Tyne, along the river Thames in London, using coal shipped from the North East, and around Stourbridge in the west Midlands. Newcastle developed as a centre for the making of broad glass by the 1640s, challenged by Stourbridge by the end of the 17th century. London developed as a maker of crown and cast plate glass, for the upper end of the market. So successful were the Newcastle and Stourbridge manufacturers in controlling their costs that by late in the 17th century broad glass was being sold at 30-50% of the price of crown glass.

| Crown & Plate | Window [ie Broad] | Window/Broad & Bottles | |

|---|---|---|---|

| London area | 5 | ||

| Bristol area | 2 | ||

| Shropshire | 1 | ||

| Stourbridge | 7 | ||

| Newcastle | 6 |

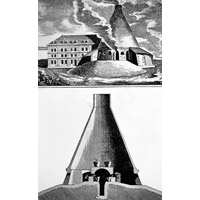

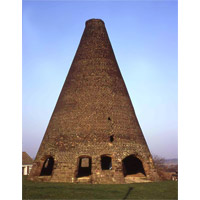

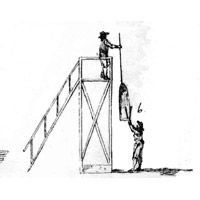

The ability to produce broad glass cheaply derived from developments in the technology of manufacture. Compositions evolved from the high-lime/low-alkali glasses typical of the 17th century to the mixed-alkali compositions found in 18th-century glass. Coal-fired furnaces increased in size over the 17th century, and the trend accelerated with the use of tall conical structures (Figs 13 and 14), which induced draught through furnaces and air-intake flues larger than those which had evolved from the traditional wood-fired furnaces (Crossley 2003). Glass was melted in crucibles of increasing size, from which molten glass was gathered in amounts which allowed larger cylinders to be blown. This was assisted by the practice of swinging the bubbles of glass over pits or from platforms (Fig. 15), to give longer cylinders which were cut and flattened into large sheets of broad glass. Glass makers used new materials for the flat surfaces on which broad-glass sheets were flattened. These were traditionally of stone and known as marvers, but during the 18th century cast iron, sheets of thick plate-glass and clay beds were used.

∧ Back to top4. The end of broad glass production in Britain

In the 19th century, the manufacture of broad glass was mechanised. In the 1830s the midlands glass makers Chance Brothers developed the mechanical handling of cylinders too large to be manipulated by the glass blower. From the 1850s onwards attempts were made to elongate glass cylinders mechanically, successfully achieved from 1894 under Lubbers’ patent (Cable 2004).

However, the manufacture of broad glass was challenged by that of sheet, where the glass was mechanically drawn from tank furnaces rather than crucibles. The successful development of sheet glass by Pilkingtons of St Helens, Lancashire, from the 1850s brought about the end of broad glass manufacture on any scale. Such broad glass as has been produced over the 20th century has been for the replacement market, for windows where authentic replication of original panes has been required on conservation grounds.

∧ Back to topReferences

Berg T. and P. (eds), 2001,

R. R. Angerstein’s Illustrated Travel Diary 1753-1755, London.

Cable M., 2004,

“The development of flat glass manufacturing processes”, Transactions of the Newcomen Society 74, 19-43.

Crossley D., 1987,

“Sir William Clavell’s glasshouse at Kimmeridge, Dorset: the excavations of 1980-81”, The Archaeological Journal 144, 340-382.

Crossley D., 1994,

“The Wealden glass industry re-visited”, Industrial Archaeoology Review 17/1, 64-74.

Crossley D., 2003,

“The archaeology of the coal-fuelled glass industry in Britain”, The Archaeological Journal 160, 160-199.

Godfrey E. S., 1974,

The Development of English Glassmaking 1560-1640, Oxford.

Houghton J., 1696,

Letters for the improvement of commerce and trade (London 1696; reprinted in Hartshorne A., Old English Glasses, London 1897, p. 457).

Louw H., 1991,

“Window-glass making in Britain c. 1660 - c. 1860 and its architectural impact”, Construction History 7, 47-68.